cooperatives in a time where it feels like we're all fending for ourselves

A recent trip to the Park Slope Food Co-op and a discussion with one if its founders has me reflecting on why this feels so novel in America

Founded in 1973, the Park Slope Food Cooperative (Co-op) may be the most successful and longest running cooperative grocery store in the United States. First situated on the upper floor of a community center 50+ years ago, it’s now greatly expanded and remains a staple in Park Slope with anywhere from 14,000 to 16,000 members at any given time. There are no customers here, only member-owners (and only member-owners can shop here). When a member joins, they pay a $100 investment into the co-op that they receive back when (if) they leave the co-op. For individuals on certain kinds of income-based assistance (for example, SNAP), the joining fee is $5 and the refundable member investment is $10. While 25% of the labor to run the store is done by paid staff, the remaining labor is done by member-owners themselves. This is unique as it is one of the few co-ops in America that is sticking to its member work requirements. Members travel from the far reaches of the city and sometimes out of state to fulfill their work requirement shifts at 4-6 week intervals and shop.

I had the opportunity last week to tour the co-op and speak with Joe Holtz, one of the founders. We covered a range of topics, including finances, food waste and lessons-learned from COVID. We also discussed how cooperatives in Europe, even those with member work requirements, have been successful but how that same model has not made headway here in the United States. The Park Slope Co-op, however, appears to be the exception, despite occasional pushback on the work requirement.

Co-ops…so what’s the appeal?

Reasonable Prices

I noticed the prices were much lower than the average grocery store in New York City. That’s because the Park Slope Co-op caps their product markup at 25% (formerly 21% until COVID strained the business).

So now, a math exercise…my favorite yogurt, La Fermiere is $2.63 at the Park Slope Co-op (Please note: I am choosing this product as an example since the price appears to be relatively stable store to store over time whereas other products tend to fluctuate). At a 25% markup, that leaves the wholesale price of the yogurt to be roughly $2.10 per container. I know that Whole Foods sells these yogurts for $3.49 a container and other grocery stores in the city retail them for $4.00 a container. That means that for this product, Whole Foods is putting a 66% markup on the yogurt and other stores are putting an 89% markup on the product.

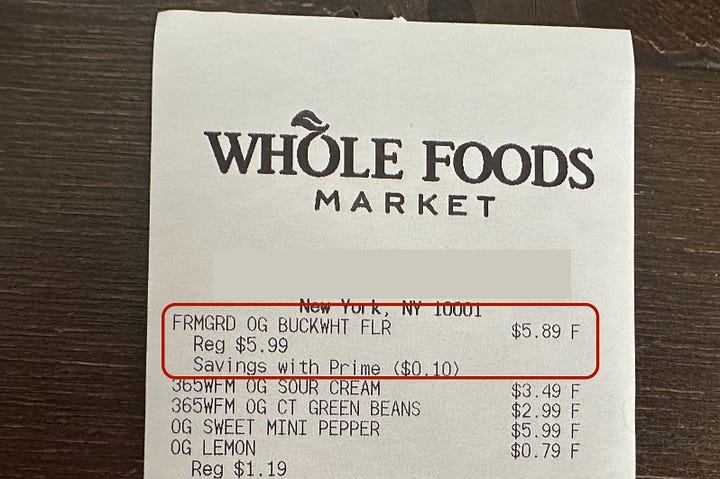

Let’s look at another example, this time of a locally-sourced pantry staple: flour. Farmers Ground flour retails at Whole Foods for $5.99 a package. At the Co-Op, it’s $4.21…that’s a 30% difference in price from one store to another. With the cap on markups, coupled with concerns about dynamic grocery pricing at some big-box stores, it is understandable why lower product pricing is a large draw.

It is also worth noting that the aforementioned markup increase from 21% to 25% was not taken lightly by the cooperative. To ensure that those who received income assistance were not disproportionately affected monetarily, the co-op devised a way to ensure that the prices those individuals paid remained the original rate, not the increased rate. Keeping people front in center with how the co-op runs its business leads me to my next point…

A Different Business Model: Member Ownership

While membership-based shopping is not a novel idea (i.e. Costco), the cooperative ownership model is different. Costco is owned by shareholders and member fees are an income stream (members may be shareholders and visa versa, but the definition of a member and a shareholder are distinct). A cooperative is owned, in the case of Park Slope, by its members and the membership fee is your financial investment into the ownership of the business. At Park Slope Coop, a member and a shareholder are the same. This concept can be structured in different ways. For example, Organic Valley is owned by the farmers that provide the milk. As an individual, you interact with businesses differently if you have an ownership stake. On the flip side, the business makes very different decisions depending on who owns them. For example, grocery stores that are owned by shareholders and large executive teams will make decisions skewed primarily around profit maximization and increasing the value of the business. That, inevitably, will provide a different experience than a grocery store that is owned by the individuals that shop there.

Instead of shareholders, larger decisions for the co-op are made or approved by the monthly General Meeting—which is open to all members. Every member who attends gets one vote. That is why, for one example, the co-op does not order food items with artificial colors, artificial preservatives or fats, bleaching agents, and other additives. Members “expressed the desire for a stricter standard than the FDA provides” so that is what they got (if you want a refresher on food additives, check out one of our first posts here). Imagine what it would take for a big-box store to make that kind of change. It’s a very different kind of influence and process.

Food is Community

It is no secret that America is enduring a loneliness epidemic, affecting nearly half of American adults. Participation in community groups has declined significantly since the 1970s, contributing a rise of loneliness according to the U.S. Surgeon General. Coincidentally - or intentionally, that timing coincides with the founding of Park Slope Cooperative. For many individuals both then and now, being a part of a cooperative is one way to fill that loneliness gap and create a sense of belonging. Particularly if that cooperative has work shift requirements that get you in person, working with others in your community, to do a range of tasks to support the co-op - from slicing and weighing cheese to working the checkout. Holz discussed how many members operate in the same group shifts every few weeks, creating bonds with other individuals on the same shift. Social events such as food classes, concerts, and parties are another way members can build connections with one another. Marriages between members that have gotten to know each other have been known to occur at the Park Slope Co-op.

These people-centric values seep their way into other elements of the co-op. There is retirement, bereavement, and parental leave (a full year!) from work requirements. All food that did not sell but is still good to eat gets donated to community partners. All products that cannot be sold or donated get composted in local community gardens. If those gardens need new composting equipment, the co-op pays for it. The bottom line here is that community is not an afterthought - it is the backbone by which the co-op operates and which is arguably what has kept it so successful for 50+ years.

Closing Thoughts

The Park Slope Coop shows that a business can be profitable, nurture their community, and provide competitive prices on food items that consumers trust and are oftentimes local. On a national scale, REI Cooperative has made a name for itself as the premier place to get outdoor gear and it’s owned by its members. All across Europe, more co-ops closely modeled after the Park Slope co-op (i.e., with work requirements) have been taking off whereas here, most co-ops never implement or have removed the work requirements. What we perhaps lose with the predominant U.S. model is that lack of collective community support.

I will leave you with this: How we procure and consume food can say a lot about our individual values around food systems, representation, health, equity and more. Think about how you shop, particularly for food. Do you have access to and the ability to support local farmers? If you’re near a co-op, can you check that out? Do you grow some of your own food and share some with your neighbors? Is the healthiest food too expensive to routinely buy but junk food is plentiful and cheap? Let’s talk about it.

What are your thoughts on co-ops? How do you live your values through your food? Drop a comment and let us know.

In what's considered rural suburbia where I live, CSA's (Community Supported Agriculture-similar to a co-op in the city) are an option. You can buy a full or half share of the farm's produce per growing season and get locally grown vegetables from that farm weekly. If you do not like something in your weekly haul you can put it in the trade basket and in turn choose a different one in exchange from the basket or try something new that you may not have previously considered. It's a nice way to get farm fresh vegetables while supporting local farms.

I think grocery today, cooperative or not, is a highly specialized entity managing supply chains, waste, automations etc which requires a distinct community, likely with some expert staff, to support it...not much available here